Can "It" Happen Here?

By John Mauldin

October 15, 2011

>

Can "It" Happen Here?

How Could This All Happen?

Currencies, Culture, and Chaos

What Causes Hyperinflation?

A Very Frank Idea

But What About the $70 Trillion in Off-Balance-Sheet Debt?

New York, London, South Africa, and the Future

>

“Bankruptcies of governments have, on the whole, done less harm to mankind than their ability to raise loans.”

- R.H. Tawney, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, 1926

“By a continuing process of inflation, government can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens.

- John Maynard Keynes, Economic Consequences of Peace

“Unemployed men took one or two rucksacks and went from peasant to peasant. They even took the train to favorable locations to get foodstuffs illegally which they sold afterwards in the town at three or fourfold the prices they had paid themselves. First the peasants were happy about the great amount of paper money which rained into their houses for their eggs and butter… However, when they came to town with their full briefcases to buy goods, they discovered to their chagrin that, whereas they had only asked for a fivefold price for their produce, the prices for scythe, hammer and cauldron, which they wanted to buy, had risen by a factor of 50.”

- Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday, 1944.

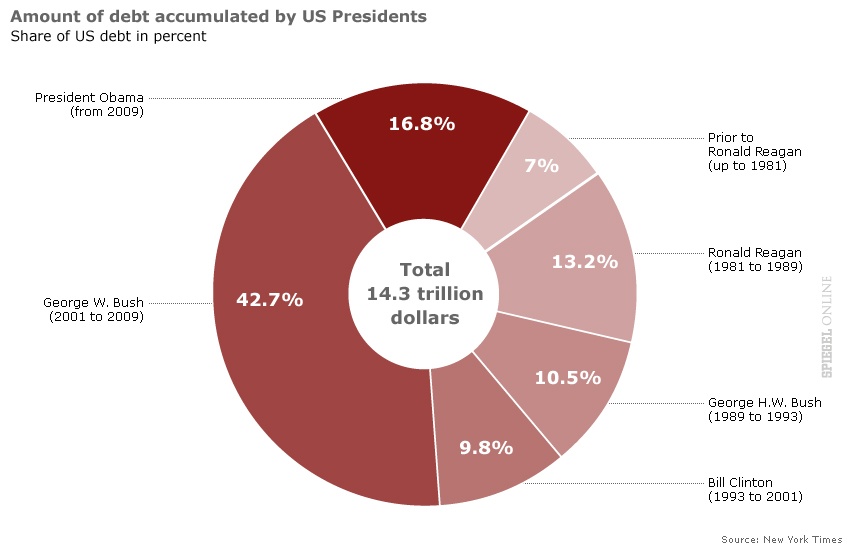

The beginning of the end of the Weimar Republic was some 89 years ago this week. There is a stream of opinion that the US is headed for the same type of end. How else can it be, given that we owe some $75-80 trillion dollars in the coming years, over 5 times current GDP and growing every year? Remember the good old days of about 5-6 years ago (if memory serves me correctly) when it was only $50 trillion? With a nod to Bernanke’s helicopter speech, where he detailed how the Fed could prevent deflation, I ask the opposite question, “Can 'it’ (hyperinflation) really happen here?” I write this on a plane flying to NYC, with a tighter deadline than normal, so let’s see how far we can get. More on where I’m heading at the end of the letter.

But first, let me quickly call to your attention a speaking engagement that I’m doing November 9 in Atlanta. It is for Hedge Funds Care, and it’s a wonderful event for a children’s charity. If you can make it, I hope to see you there. You can learn more and register at http://www.hedgefundscare.org/event.asp?eventID=74.

I was inspired for this week’s letter by a piece by Art Cashin (whom I will get to have dinner with Monday). His daily letter always begins with an anecdote from history. Yesterday it was about Weimar, told in his own inimitable style. So without any edits, class will commence, with Professor Cashin at the chalk board.

An Encore Presentation

By Art Cashin

Originally, on this day (-2) in 1922, the German Central Bank and the German Treasury took an inevitable step in a process which had begun with their previous effort to “jump start” a stagnant economy. Many months earlier they had decided that what was needed was easier money. Their initial efforts brought little response. So, using the governmental “more is better” theory they simply created more and more money.

But economic stagnation continued and so did the money growth. They kept making money more available. No reaction. Then, suddenly prices began to explode unbelievably (but, perversely, not business activity).

So, on this day government officials decided to bring figures in line with market realities. They devalued the mark. The new value would be 2 billion marks to a dollar. At the start of World War I the exchange rate had been a mere 4.2 marks to the dollar. In simple terms you needed 4.2 marks in order to get one dollar. Now it was 2 billion marks to get one dollar. And thirteen months from this date (late November 1923) you would need 4.2 trillion marks to get one dollar. In ten years the amount of money had increased a trillion fold.

Numbers like billions and trillions tend to numb the mind. They are too large to grasp in any “real” sense. Thirty years ago an older member of the NYSE (there were some then) gave me a graphic and memorable (at least for me) example. “Young man,” he said, “would you like a million dollars?” “I sure would, sir!” I replied anxiously. “Then just put aside $500 every week for the next 40 years.” I have never forgotten that a million dollars is enough to pay you $500 per week for 40 years (and that’s without benefit of interest). To get a billion dollars you would have to set aside $500,000 dollars per week for 40 years. And a…..trillion that would require $500 million every week for 40 years. Even with these examples, the enormity is difficult to grasp.

Let’s take a different tack. To understand the incomprehensible scope of the German inflation maybe it’s best to start with something basic….like a loaf of bread. (To keep things simple we’ll substitute dollars and cents in place of marks and pfennigs. You’ll get the picture.) In the middle of 1914, just before the war, a one pound loaf of bread cost 13 cents. Two years later it was 19 cents. Two years more and it sold for 22 cents. By 1919 it was 26 cents. [Double in value, or a "mere" 12% compound inflation –JM.] Now the fun begins.

In 1920, a loaf of bread soared to $1.20, and then in 1921 it hit $1.35. By the middle of 1922 it was $3.50. At the start of 1923 it rocketed to $700 a loaf. Five months later a loaf went for $1200. By September it was $2 million. A month later it was $670 million (wide spread rioting broke out). The next month it hit $3 billion. By mid month it was $100 billion. Then it all collapsed [as if a roughly 8 billion times rise in cost wasn't already collapse! Hint of irony here. – JM]

Let’s go back to “marks”. In 1913, the total currency of Germany was a grand total of 6 billion marks. In November of 1923 that loaf of bread we just talked about cost 428 billion marks. A kilo of fresh butter cost 6000 billion marks (as you will note that kilo of butter cost 1000 times more than the entire money supply of the nation just 10 years earlier).

In 1913 Germany had a solid, prosperous, advanced culture and population. Like much of Europe it was a monarchy (under the Kaiser). Then, following the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914, the world moved toward war. Each side was convinced the other would not dare go to war. So, in a global game of chicken they stumbled into the Great War.

[Side note: So convinced were the bond markets that war was not possible that bonds were still selling at normal prices. War was simply inconceivable. Bad call. - JM]

The German General Staff thought the war would be short and sweet and that they could finance the costs with the post war reparations that they, as victors, would exact. The war was long. The flower of their manhood was killed or injured. They lost and, thus, it was they who had to pay reparations rather than receive them.

Things did not go badly instantly. Yes, the deficit soared but much of it was borne by foreign and domestic bond buyers. As had been noted by scholars…..”The foreign and domestic public willingly purchased new debt issues when it believed that the government could run future surpluses to offset contemporaneous deficits.” In layman’s English that means foreign bond buyers said – “Hey this is a great nation and this is probably just a speed bump in the economy.” (Can you imagine such a thing happening again?)

When things began to disintegrate, no one dared to take away the punchbowl. They feared shutting off the monetary heroin would lead to riots, civil war, and, worst of all communism. So, realizing that what they were doing was destructive, they kept doing it out of fear that stopping would be even more destructive.

If it is difficult to grasp the enormity of the numbers in this tale of hyper-inflation, it is far more difficult to grasp how it destroyed a culture, a nation and, almost, the world.

People’s savings were suddenly worthless. Pensions were meaningless. If you had a 400 mark monthly pension, you went from comfortable to penniless in a matter of months. People demanded to be paid daily so they would not have their wages devalued by a few days passing. Ultimately, they demanded their pay twice daily just to cover changes in trolley fare. People heated their homes by burning money instead of coal. (It was more plentiful and cheaper to get.)

The middle class was destroyed. It was an age of renters, not of home ownership, so thousands became homeless.

But the cultural collapse may have had other more pernicious effects.

Some sociologists note that it was still an era of arranged marriages. Families scrimped and saved for years to build a dowry so that their daughter might marry well. Suddenly, the dowry was worthless – wiped out. And with it was gone all hope of marriage. Girls who had stayed prim and proper awaiting some future Prince Charming now had no hope at all. Social morality began to collapse. The roar of the roaring twenties began to rumble.

All hope and belief in systems, governmental or otherwise, collapsed. With its culture and its economy disintegrating, Germany saw a guy named Hitler begin a ten year effort to come to power by trading on the chaos and street rioting. And then came World War II.

That soul-wrenching and disastrous experience with inflation is seared into the German psyche. It is why the populace is reluctant to endorse the bailout. It is also why all the German proposals have each country taking care of its own banks. (It gives them more control.) The French plans tend to socialize the bailout. There’s more disagreement in these plans than the headlines would indicate.

To celebrate have a Jagermeister or two at the Pre Fuhrer Lounge and try to explain that for over half a century America’s trauma has been depression-era unemployment while Germany’s trauma has been runaway inflation. But drink fast, prices change radically after happy hour.

We spent a whole chapter writing about inflation and hyperinflation in Endgame, which I think highlights the topic rather well (http://www.amazon.com/endgame). Let me quote a few paragraphs.

“We know that the world is drowning in too much debt, and it is unlikely that households and governments everywhere will be able to pay down that debt. Doing so in some cases is impossible, and in other cases it will condemn people to many hard years of labor in order to be debt-free. Inflation, by comparison, appears to be the easy way out for many policy makers.

“Companies and households typically deal with excessive debt by defaulting; countries overwhelmingly usually deal with excessive debt by inflating it away. While debt is fixed, prices and wages can go up, making the total debt burden smaller. People can’t increase prices and wages through inflation, but governments can create inflation and they’ve been pretty good at it over the years. Inflation, debt monetization and currency debasement are not new. They have been used for the past few thousand years as means to get rid of debt. In fact, they work pretty well.

“The average person thinks that inflation comes from 'money printing.’ There is some truth to this, and indeed the most vivid images of hyperinflation are of printed German Reichmarks being burnt for heat in the 1920s or Hungarian Pengos being swept up in the streets in 1945.

“You don’t even have to go that far back to see hyperinflation and how brilliantly it works at eliminating debt. Let’s look at the example of Brazil, which is one of the world’s most recent examples of hyperinflation. This happened within our lifetimes. In the late 1980s and 1990s it very successfully got rid of most of its debt.

“Today Brazil has very little debt as it has all been inflated away. Its economy is booming, people trust the central bank and the country is a success story. Much like the United States had high inflation in the 1970s and then got a diligent central banker like Paul Volcker, in Brazil a new government came in, beat inflation, produced strong real GDP growth and set the stage for one of the greatest economic success stories of the past two decades. Indeed the same could be said of other countries like Turkey that had hyperinflation, devaluation, and then found monetary and fiscal rectitude.

“In 1993 Brazilian inflation was roughly 2,000%. Only four years later, in 1997 it was 7%. Almost as if by magic, the debt disappeared. Imagine if the US increased its money supply which is currently $900 billion by a factor of 10,000 times as Brazil’s did between 1991 and 1996. We would have 9 quadrillion USD on the Fed’s balance sheet. That is a lot of zeros. It would also mean that our current debt of thirteen trillion would be chump change. A critic of this strategy for getting rid of our debt could point out that no one would lend to us again if we did that. Hardly. Investors, sadly, have very short memories. Markets always forgive default and inflation. Just look at Brazil, Bolivia, and Russia today. Foreigners are delighted to invest in these countries.

“The endgame is not complicated under inflation/hyperinflation. Deflation is not inevitable. Money printing and monetization of government debt works when real growth fails. It has worked in countless emerging market economies (Zimbabwe, Ukraine, Tajikistan, Taiwan, Brazil, etc.). We could even use it in the US to get rid of all our debts. It would take a few years, and then we could get a new central banker like Volker to kill inflation. We could then be a real success story like Brazil.

“Honestly, recommending hyperinflation is tongue in cheek. But now even serious economists are recommending inflation as a solution. Given the powerful deflationary forces in the world, inflation will stay low in the near term. This gives some comfort to mainstream economists who think we can create inflation to solve the debt problem in the short run. The International Monetary Fund’s top economist, Olivier Blanchard, has argued that central banks should target a higher inflation rate than they do at present in order to avoid the possibility of deflation. Economists like Paul Krugman, a Nobel Prize winner, and Olivier Blanchard argue that central banks should raise their inflation targets to as high as 4%. Paul McCulley argues that central banks should be 'responsibly irresponsible.’

“Peter Bernholz wrote the bible on inflation and hyperinflation, called Monetary Regimes and Inflation: History, Economic and Political Relationships. He writes about 29 periods of hyperinflation. What causes such a spectacular increase in prices? Bernholz has explained the process very elegantly.

“Bernholz argues that governments have a bias towards inflation. The evidence doesn’t disagree with him. The only thing that limits a government’s desire for inflation is an independent central bank. After looking at inflation across all countries and analyzing all hyperinflationary episodes, the lessons are the following:

1. Metallic standards like gold or silver standard show no, or a much smaller, inflationary tendency than discretionary paper money standards

2. Paper money standards with central banks independent of political authorities are less inflation-based than those with dependent central banks.

3. Currencies based on discretionary paper standards and bound by a regime of a fixed exchange rate to currencies, which either enjoy a metallic standard or, with a discretionary paper money standard, an independent central bank, show also a smaller tendency towards inflation, whether their central banks are independent or not.

“Bernholz examined twelve of the twenty-nine hyperinflationary episodes where significant data existed. Every hyperinflation looked the same. 'Hyperinflations are always caused by public budget deficits which are largely financed by money creation.’ But even more interestingly, Bernholz identified the level at which hyperinflations can start. He concluded that 'the figures demonstrate clearly that deficits amounting to 40 percent or more of expenditures cannot be maintained. They lead to high inflation and hyperinflations….’ Interestingly, even lower levels of government deficits can cause inflation. For example, 20% deficits were behind all but four cases of hyperinflation.

“Stay with us here, because this is an important point. Most analysts quote government deficits as a percentage of GDP. They’ll say, 'The US has a government deficit of 10% of GDP.’ While this measure makes some sense, it doesn’t tell you how big the deficit is relative to expenditures. The deficit may be 10% the size of the US economy, but currently the US deficit is over 30% of all government spending. That is a big difference.”

I am confronted all the time on the road by investors who want to know my basis for stating that we will not see hyperinflation in the US. I am good friends with many who believe it is the only way the US can end up, given the size of the current off-balance-sheet debacle. “End of America” Porter Stansberry, Doug Casey and David Galland (see below), Peter Schiff, Bill Bonner, and a host of gold bugs see no other way out. They look at history as written by Bernholz and see the proverbial writing on the wall. It is totally decipherable by them. I remain very unconvinced.

The US Federal Reserve system is different from most central banks, whether it is independent or not. It is composed of 12 separate regional banks, each of which has its own board, which appoints its regional president. The regions each get a certain number of rotating votes in the FOMC meetings, along with the appointed Fed governors. But they all get to participate in FOMC meetings and offer opinions. And the presidents certainly talk with each other. The last two meetings have seen the unusual circumstance of three dissenting votes.

These regional boards comprise local business leaders, some academics, and community leaders. They have to go back and work and live in their communities. They don’t get to retire to an ivory tower and tenure, like many Fed governors. They see the real world, or at least their parts of it, and the boards have become very diverse over time.

Hyperinflation requires a central bank to willingly commit economic suicide. Typically, that happens at the behest of an authoritarian government. Under our current system, I can’t see that happening. The hue and cry would be very loud and long and early. If you think Fisher et al. are vocal today, think about their response to really aggressive printing. I am not talking about something on the order of QE2, a BB gun as compared to a bazooka. I am talking about real printing.

It is not just a few vocal regional Fed presidents, of whom Fisher is the most eloquent. Even Bernanke has been talking about the limits of monetary policy and the need for the fiscal house to be put in order.

If Bernanke and his fellow Keynesians could whip up 4-5% inflation for a few years, would they do it? I think so, although they would publicly demur. But that is a far cry from 10% and even further from the 50% that would be needed to really ignite hyperinflation. I doubt they have the stomach for that, even in the face of a serious recession. The memories of the ’70s are still part of our genetic make-up.

But could they print a whole lot more than one can imagine now, without unleashing the inflation demon? The simple answer is yes, and for that rationale we go back to the ’30s and Irving Fisher, who gave us the classic equation of the link between money supply and inflation and the velocity of money (how fast money moves through an economy).

Inflation is a combination of the money supply AND the velocity of money. In short, if the velocity of money is falling, the Fed can print a great deal of money (expanding its balance sheet) without bringing about inflation. Remember the above instance, where workers wanted to get paid twice a day? That was a case of both rising money supply and rising velocity of money, a deadly combination. I have written several e-letters about the velocity of money, if you want more in-depth analysis. If this is something you do not understand, I suggest you take the time; otherwise you will not get the background of the argument. Here are a couple links to letters where I explain the velocity of money:

http://www.johnmauldin.com/frontlinethoughts/the-implications-of-velocity-mwo031210

http://www.johnmauldin.com/frontlinethoughts/the-velocity-factor-mwo120508

When do we see a seriously falling velocity of money? At the end of debt supercycles, where deleveraging is the order of the day. Which is where we are today in the US. Look at the graph below (from my friend Lacy Hunt at Hoisington Asset Management). Notice that the late ’70s saw a rising money supply and rising velocity of money. And voila, we got inflation in the US. Notice that now velocity is falling and, as Lacy points out, the velocity is mean reverting over very long periods of time, so we can expect it to go lower. Also remember that the US government (at the federal level) has yet to really begin to get its fiscal house in order. (Although state and local government have combined to cut deficits $200 billion a year through a combination of spending cuts and tax increases, or over 1% of GDP, which has been a serious headwind with more cuts and tax increases to come.)

What could change my mind? If the (how to say this politely?) ill-conceived (stronger words come to mind) proposal by Financial Services Committee ranking member Barney Frank (D-Mass) were to see the light of day, I would get very concerned. According to Bloomberg and The Hill, Frank plans to submit a bill that would remove the votes of the five regional Federal Reserve presidents from the 12-member Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC), which sets interest rates, and replace them with five appointees that would be nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

Frank says “he is concerned that the process is undemocratic because the regional Fed presidents are not elected or appointed by elected representatives, and he believes that regional Fed presidents are overly likely to focus on guarding against inflation at the expense of more adequately tackling the country’s unemployment crisis.” (US News and World Report)

Basically, he wants the Fed to be subservient to the politicians. Under his proposal, the FOMC could lose what independence it has in a short time. This is part of a strain of thought that suggests that the decisions that affect all of us should be made by a few elite people who purport to understand what is going on, which coincidentally are government insiders and the academics who foster their agendas.

How did Weimar and other hyperinflation incidents occur? When power was in the hands of a few well-intentioned elites who did not understand the long-term consequences, or were acting in self-interest without transparency or any check on their decisions. The Fed is designed to be a system of checks and balances, with no one president getting to appoint all the governors (they have 14-year terms), in order to try to remove the process as much as possible from political interference. That does not mean they will make the right decisions, but in this I agree with the alarmists: history suggests that without some constraint (gold standards as an example) hyperinflations may occur.

A repeat of the ’70s? That is within the realm of possibility, but it’s certainly not a base-case scenario. Hyperinflation under our current system? I just don’t see it.

I am asked that question all the time. My answer is that it illustrates the power of “It Won’t Happen.” As in “if it can’t happen it won’t happen.” That number will never be paid, either in terms of current buying power or actual numbers or actual benefits. It can’t be. The money is not and will not be there.

The far more interesting question is what will happen when we reach the point of “won’t happen.” Will that be something we recognize before it happens and act proactively to avoid a cataclysmic event? Will we wait until the bond market jerks our chain about the fiscal crisis, which is massively stagflationary? Yes, the Fed can print to some degree, but not dealing with the crisis will ultimately force a huge restructuring of spending and taxes which, if not caught early enough, will propel us into a certain Second Great Depression. Which is why I think we will deal with it proactively in 2013, because to not do so would be folly of the worst sort. The consequences are unimaginable for the US and for the world. Think Greece, and then go downhill. All over the world.

I think more and more political leaders are beginning to understand that point. They are not happy about it. But I remain hopeful that in 2013 we can actually deal with the deficit and the debt in an orderly manner. If we do not, God help us all.

Monday I will be on Yahoo! Finance in the morning, Bloomberg Radio at 9:45, and Fox Business TV at 1:15, with meetings all day (and time for reading sandwiched in between). Then Monday night dinner with a special group of people: Art Cashin, Barry Habib, Barry Ritholtz, Dennis Gartman, Vince Farrell, and Doug Kass if he can shake free. Think we’ll talk investments and economics? Then on to Philly that night, where I speak the following morning for a group hosted by my partner Steve Blumenthal of CMG. Then back to NYC, a quick 3 PM TV gig with Canadian TV BBN, and off to JFK and London. The next month is crazy with travel. I am in London (actually Richmond) Wednesday for a 12-hour layover, where I can have a few meetings. One night in South Africa. Back home Saturday and then Monday to New Orleans and then somewhere else, etc.

But that is then. Tonight and this weekend is pure pleasure. Tiffani and I have a private dinner with Ray Kurzweil in about 10 minutes (now in car). I must admit I am a huge Ray Kurzweil groupie. Then some of the best futurists in the world will be speaking in rapid order for the next two days at the Singularity Summit, and lucky me, I get to meet them! Plus 750 attendees, who will all have their own stories, opinions, and insights. Sunday night with David Galland, head honcho of Casey Research and fellow futurist and sci-fi junkie, who is also attending the conference. He told me to read Daniel Suarez’s two books, Daemon and Freedom. They are an adrenaline rush. Must-reads, if you want to get a feeling for what it is going to be like to have change hit you seemingly all at once. I am not a fan of his dystopian vision, but it makes for gripping fiction, and the technology descriptions make the ride doubly enjoyable. Read them. Oh, and really good friend David Brin will also be there. We will celebrate our recent birthdays. And he has just finished a brilliant book that I got to read the first draft of, even before he finished. Love it! Will let you know when it is out.

And now I’m back in the room, finally getting ready to hit the send button. What a week. It was good to be with old friends Ed Easterling and David Rosenberg last night, as well as money maven Cliff Draughn, who flew in from Savannah just to be here. (Thanks Cliffie!)

I feel like I am drinking life through a fire hose, but I would not want it any other way. I am now writing a book (The Millennium Wave) about how fast change is going to happen (and that will be the topic of my speech on Sunday), but I am struggling to keep up even now! The great British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury is said to have remarked to Her Majesty Queen Victoria, “Change, change, why do we need more change? Aren’t things bad enough already?” But the changes coming are something not even a conservative English lord can hold back, so better to learn to surf the inevitable.

Have a great week. Other than sleeping three nights in four on airplanes (what idiot designed this schedule? I would fire him if I only could!) I am going to have a good one.

Your ready for some future thinking analyst,

John Mauldin

John@FrontlineThoughts.com

Source: JohnMauldin.com (http://s.tt/13w6y)