Macro Factors and their impact on Monetary Policy

Macro Factors and their impact on Monetary Policy

the Economy, and Financial Markets

MacroTides macrotides1@gmail.com

Investment letter – October 21, 2011

,

Winter is Right Around the Corner

We grew up in the Midwest, where the winters are often measured by wind chill factors below zero and multiple layers of clothing just to prevent frostbite. In most years, there is a day in March when the temperature 'soars' to 50 degrees. On those days it was not uncommon to see people walking around in shirt sleeves, relishing the opportunity to savor the first hint of spring. Months later on July 4, thousands of people would gather near Lake Michigan to watch the fireworks display. Too often, the weather failed to cooperate, and by dusk the temperature would have fallen to 60 degrees. Looking around, everyone was bundled up in sweatshirts, sweaters, stocking caps and gloves, even though it was actually a bit warmer than the spring like day in March. The same phenomenon happens with market expectations.

After a series of punk economic reports in August and September, most investors were prepared for the onset of another recession as October began. Instead of a blizzard of more bad news, reports on manufacturing, retail sales, and employment, failed to confirm that a recession had begun. The gloom was replaced by a glimmer of hope. Maybe there would be no recession after all! If this assumption proves true, the recent rally in the stock market is justified, and the market will hold on to its gains. On the other hand, if these reports were simply a phantom spring like day in the middle of winter, the stock market could prove more vulnerable to disappointment in coming months. The recession in 2001-2002 lasted just eight months and was quite shallow, but earnings estimates proved to be 25% too optimistic. In the "Great Exhale" recession of 2008-2009 estimates were off by 40%. We think the U.S. economy will weaken in the first half of 2012, potentially flirting with at least one quarter of negative growth. This scare will cause analysts to cut earnings projections by 15% or more, and should cause the stock market to fall below the lows of October 4.

Manufacturing has been one of the few sectors of legitimate strength since the recession ended in June 2009, and will likely remain resilient through the end of this year due to a tax credit that expires on December 30, 2011. This tax credit allows companies to write off any business investment booked before the end of this year. If a business is planning on making $50 million in business investments in the first half of 2012, they would be crazy not to accelerate a large portion of the investment before year end, since they would be able to write off 30% of the investment on their 2011 taxes. (or whatever their tax bracket) The investment tax credit will pull demand forward into 2011, just like the Cash for Clunkers and first time home buyers tax credit did in 2009 and 2010. In the short run, manufacturing activity will look stronger, but after January 1, business investment will drop sharply.

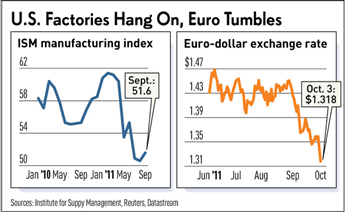

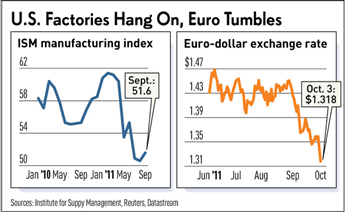

The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Index rose to 51.6 in September. Any reading above 50 indicates that manufacturing in the U.S. is expanding. The ISM Index will likely hold above 50 through December as companies take advantage of a tax credit that expires on December 30, 2011 for business equipment investments. Within the September report, there were some cracks. New orders declined for a third month in a row, and order back logs fell to 41.5, the lowest since April 2009. The recent low in the ISM Index was well below the low reached when the economy slowed during the summer of 2010. Although the tax credit should give manufacturing a temporary boost, the overall trend is weakening. In addition, the slowdown in manufacturing is not just happening in the U.S. JP Morgan's global manufacturing gauge fell .3 in September to 49.9, contracting for the first time since June 2009.

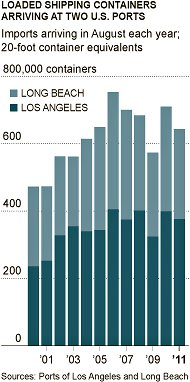

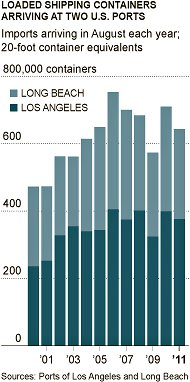

Retail sales gained 1.1% in September, and excluding autos were ahead .6%. This report heartened economists, since it showed resilience in consumer spending, which accounts for 70% of GDP. Retailers tracked by Thomson Reuters reported a 5.1% increase in same store sales in September. This led retail analysts to increase their estimates for holiday sales from the 3%-4% range to 5%-6% level. We believe these targets are overly optimistic. Traditionally, retailers begin taking delivery of holiday merchandise by late October. For this to happen, orders that are placed for goods produced overseas begin to arrive at the five busiest ports in the United Sates during August and September. The rush of holiday merchandise usually causes a spike in container volume at the ports. There was no spike in shipments in August and September at any of the five ports. In fact, each of the five largest ports reported declines from 2010 levels. In Long Beach, the second busiest port, volume in August was 14.2% lower than in 2010, and September was almost 15% lighter. Los Angeles, the nation's largest port, reported 5.75% fewer containers in August. In Savannah, Georgia, imports were off by 4%, while they were down .9% in Oakland, and flat in New York and New Jersey.

Retail sales gained 1.1% in September, and excluding autos were ahead .6%. This report heartened economists, since it showed resilience in consumer spending, which accounts for 70% of GDP. Retailers tracked by Thomson Reuters reported a 5.1% increase in same store sales in September. This led retail analysts to increase their estimates for holiday sales from the 3%-4% range to 5%-6% level. We believe these targets are overly optimistic. Traditionally, retailers begin taking delivery of holiday merchandise by late October. For this to happen, orders that are placed for goods produced overseas begin to arrive at the five busiest ports in the United Sates during August and September. The rush of holiday merchandise usually causes a spike in container volume at the ports. There was no spike in shipments in August and September at any of the five ports. In fact, each of the five largest ports reported declines from 2010 levels. In Long Beach, the second busiest port, volume in August was 14.2% lower than in 2010, and September was almost 15% lighter. Los Angeles, the nation's largest port, reported 5.75% fewer containers in August. In Savannah, Georgia, imports were off by 4%, while they were down .9% in Oakland, and flat in New York and New Jersey.

There has been no pick up in railroad volumes associated with the holidays either. According to Burlington Northern Santa Fe, volumes in July, August and September were flat compared to 2010. The Ceridian-UCLA Pulse of Commerce Index, which tracks real time trucking activity, fell for the third month in a row. The index dipped .2% in July, 1.4% in August, and 1% in September. This represents an annual rate of decline of more than 10%, which was only exceeded in the 2008-2009 recession.

In late September, the International Air Transport Association reported freight utilization fell to 45% in July. (latest figures available) Freight utilization measures how full freight planes are, as well as the cargo space in passenger planes. This measure rose from under 40% in 2009 to over 50% in 2010. Given the weakness in all the other modes of shipping in August and September, air freight utilization has likely slipped below 45%. The transportation of goods by land, sea, and air represent the arterial system of economic activity domestically and internationally. These reports provide an unambiguous picture of a slowdown in economic activity in the United States and globally.

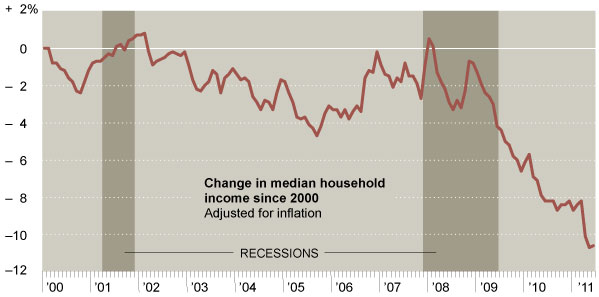

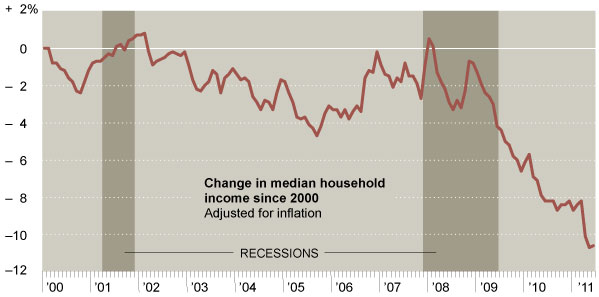

Although 103,000 jobs were created in September, the labor market remains incredibly weak, considering we are more than two years into the recovery. Since the recession ended in June 2009, the average length of time an unemployed worker has been out of work has increased from 24.1 weeks to 40.5 weeks in September, the longest in 60 years. Those who did manage to find a job made an average of 17.5% less than they had previously, according to Princeton economics professor, Henry Farber. Between June 2009 and June 2011, inflation adjusted median household income fell 6.7% to $49,909, based on monthly Census Bureau data. This decline is larger than the 3.2% decline in household income that occurred between December 2007 and June 2009, when the recession was in full bloom!

Over the last twelve months, inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price index, has increased by 3.9%. During the same period, average weekly wages rose only 2.1%. Even those with a job are finding it harder to make ends meet, since their cost of living is rising faster than their incomes. It is no surprise that consumer confidence remains at levels only previously seen during recessions. Given the ongoing weakness in job growth and disposable income, it is difficult to see holiday sales increasing 5%-6% this year.

Over the last 60 years, the Federal Reserve's most powerful monetary tool has been raising and lowering the cost of money to manage the economy. Short term rates have been held just above 0% for three years, and the Fed has indicated they will hold them steady for another two years. With inflation at 3.9%, the effective 'real' Federal funds rate is a negative 3.6%. Despite this unprecedented level of monetary accommodation, the current recovery has been anemic, averaging less than half the average GDP growth since World War II. With its most powerful monetary tool neutered, the Federal Reserve has executed two Quantitative Easing programs to spur a pickup in job growth, housing, and overall economic growth. These extraordinary measures have failed. They did, however, contribute to an overall increase in the cost of living, which has only made life for the average family harder. This was surely not their intention. But the unintended consequences of desperate acts are rarely positive.

Over the last 60 years, the Federal Reserve's most powerful monetary tool has been raising and lowering the cost of money to manage the economy. Short term rates have been held just above 0% for three years, and the Fed has indicated they will hold them steady for another two years. With inflation at 3.9%, the effective 'real' Federal funds rate is a negative 3.6%. Despite this unprecedented level of monetary accommodation, the current recovery has been anemic, averaging less than half the average GDP growth since World War II. With its most powerful monetary tool neutered, the Federal Reserve has executed two Quantitative Easing programs to spur a pickup in job growth, housing, and overall economic growth. These extraordinary measures have failed. They did, however, contribute to an overall increase in the cost of living, which has only made life for the average family harder. This was surely not their intention. But the unintended consequences of desperate acts are rarely positive.

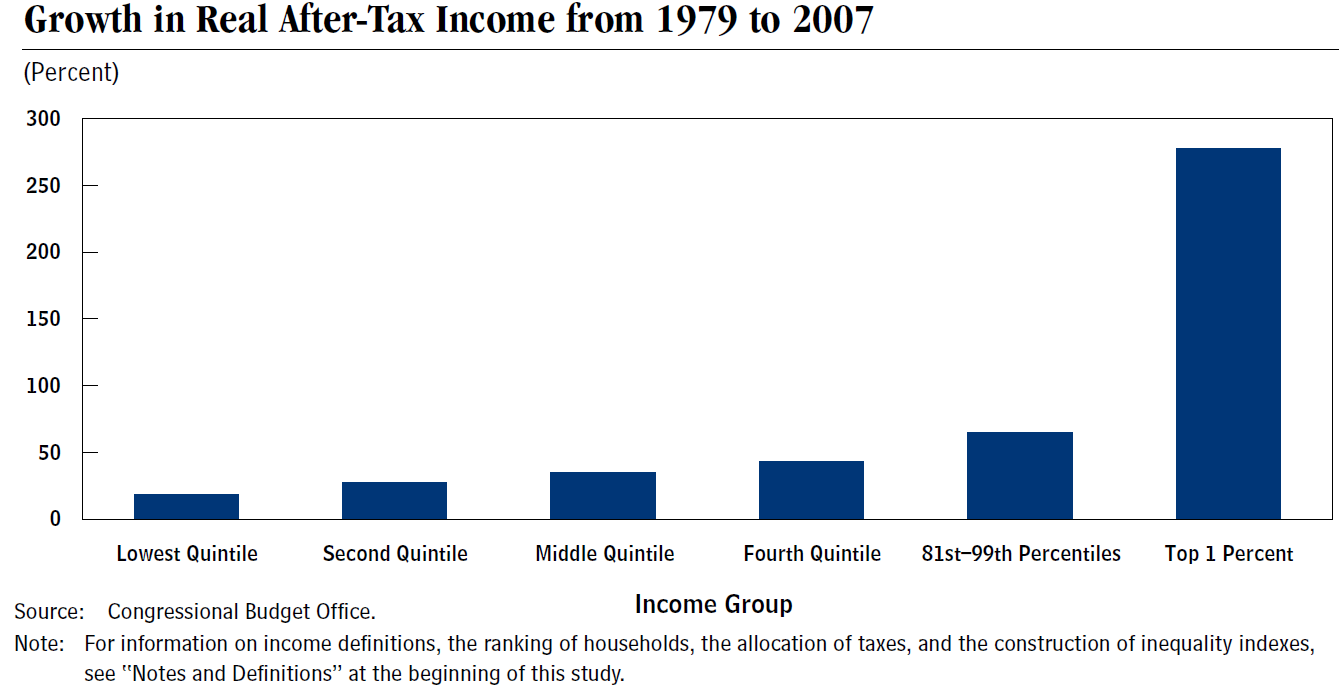

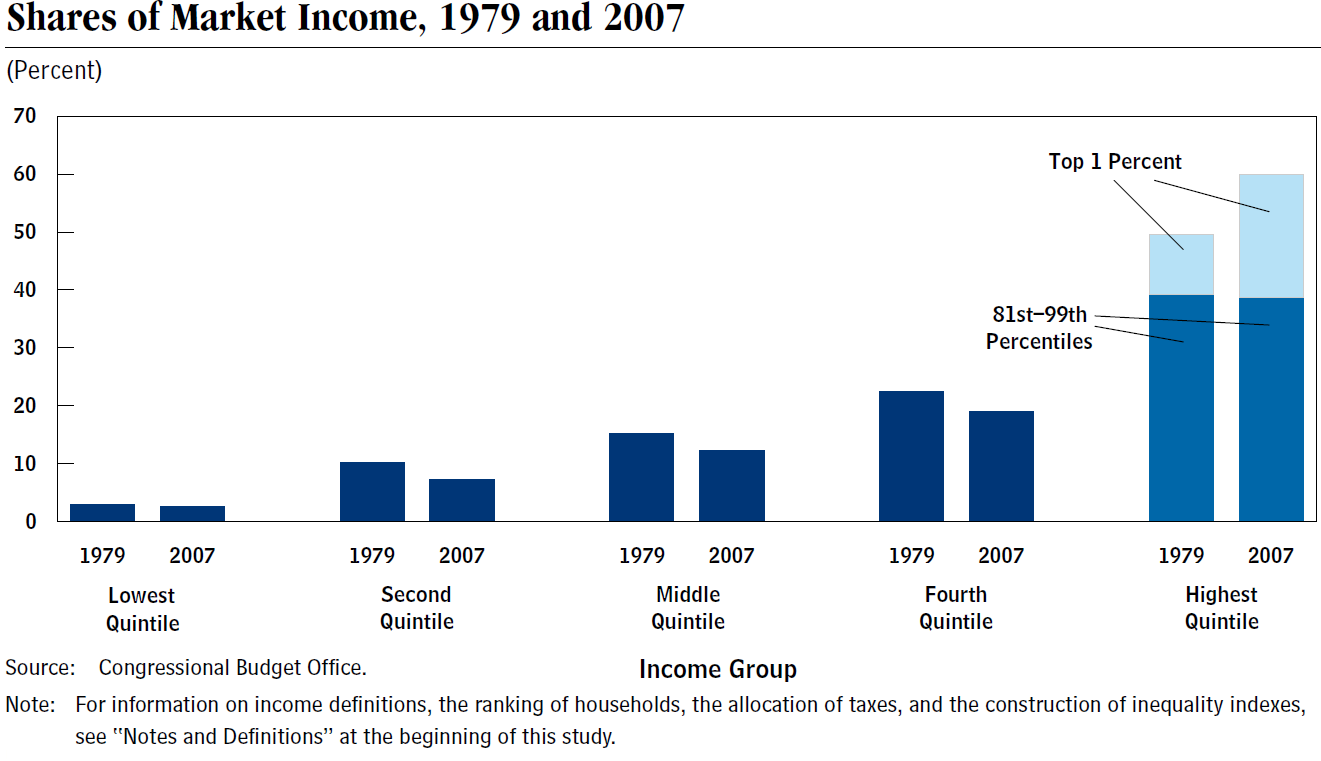

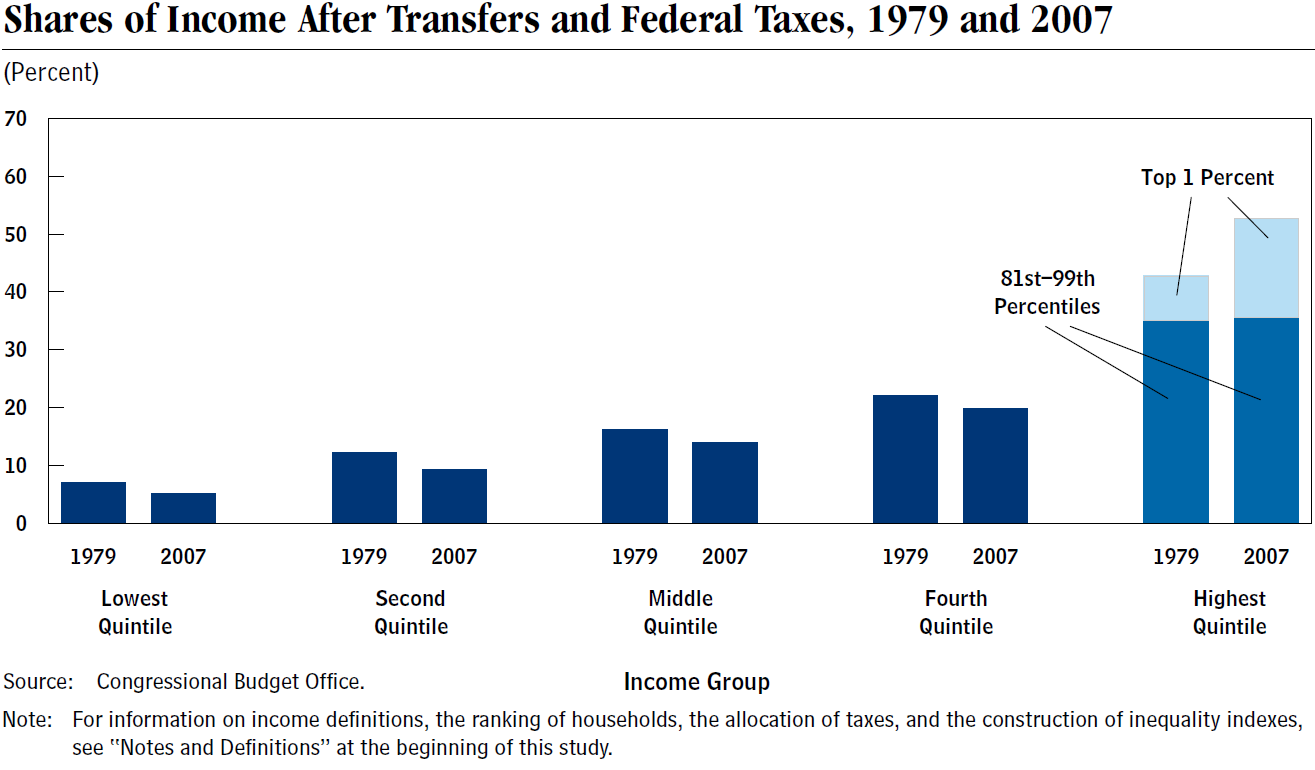

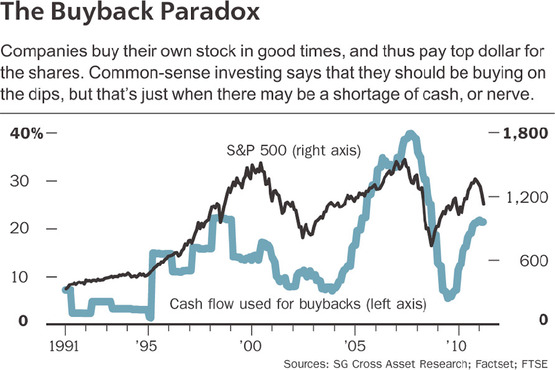

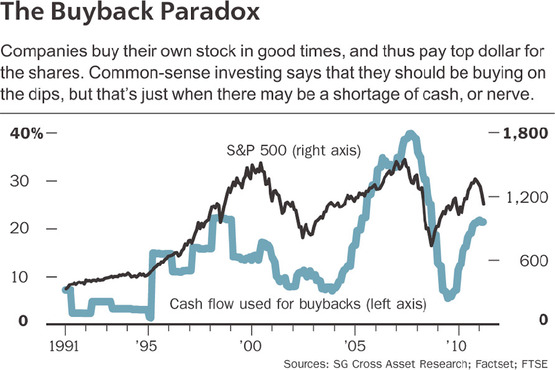

In 2010, the CEO's of S&P 500 companies earned an average of $11.4 million, or 228 times median household income of $49,909. In the 1960's, the average CEO's pay was less than 40 times the average worker's pay. A good chunk of their income is derived from stock options (average 21%), which become more valuable as their company's stock rises. According to the Federal Reserve, U.S. corporations held a record $1.93 trillion in cash on their balances at the end of 2010. There are many ways a corporation can invest their cash. They can invest in research to develop new products, or increase marketing to increase sales. They can also pay down debt, or increase dividends. Too often, companies choose to buy back their own stock, often paying more than their stock is subsequently worth. In the second quarter, S&P 500 companies spent $109 billion on buybacks, according to Standard & Poors. These purchases were not particularly well timed, since the S&P fell almost 15% in the third quarter. In 2007, companies used 40% of their cash flow for buybacks, which proved awful timing. But the stock options held in 2007 by corporate executives and company directors were likely boosted by the buybacks. If a CEO can't identify investments that will improve a company's fortunes for the long term, are they really worth $11.4 million? We doubt participants in the Occupy Wall Street movement know these statistics. But the inequality of income distribution is a structural issue that must be dealt with in coming years. We have no problem with a CEO being paid so much, if the Board of Directors and shareholders don't object. Raising taxes on these CEO's won't even bring in much tax revenue, but it will be a symbol for all those who are going through a financially difficult time.

In 2010, the CEO's of S&P 500 companies earned an average of $11.4 million, or 228 times median household income of $49,909. In the 1960's, the average CEO's pay was less than 40 times the average worker's pay. A good chunk of their income is derived from stock options (average 21%), which become more valuable as their company's stock rises. According to the Federal Reserve, U.S. corporations held a record $1.93 trillion in cash on their balances at the end of 2010. There are many ways a corporation can invest their cash. They can invest in research to develop new products, or increase marketing to increase sales. They can also pay down debt, or increase dividends. Too often, companies choose to buy back their own stock, often paying more than their stock is subsequently worth. In the second quarter, S&P 500 companies spent $109 billion on buybacks, according to Standard & Poors. These purchases were not particularly well timed, since the S&P fell almost 15% in the third quarter. In 2007, companies used 40% of their cash flow for buybacks, which proved awful timing. But the stock options held in 2007 by corporate executives and company directors were likely boosted by the buybacks. If a CEO can't identify investments that will improve a company's fortunes for the long term, are they really worth $11.4 million? We doubt participants in the Occupy Wall Street movement know these statistics. But the inequality of income distribution is a structural issue that must be dealt with in coming years. We have no problem with a CEO being paid so much, if the Board of Directors and shareholders don't object. Raising taxes on these CEO's won't even bring in much tax revenue, but it will be a symbol for all those who are going through a financially difficult time.

Europe

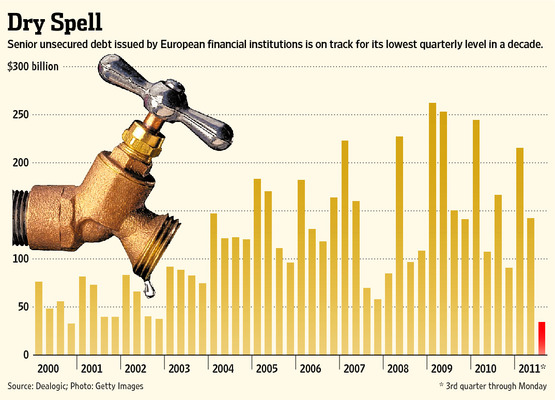

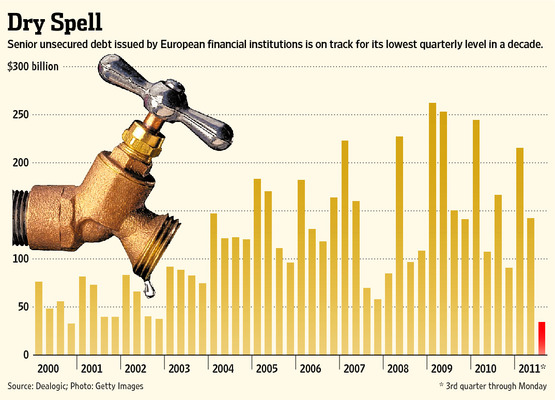

We believe the European Union is facing an insurmountable challenge that can only be partially addressed. In recent months, European banks have experienced increasing difficulty in rolling existing debt, as U.S. money market funds have significantly reduced their exposure, and banks in Europe curtailed lending to each other. The European Central Bank has addressed this problem by expanding its lending to more than $650 billion to banks in Ireland, Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and France. The bigger problem is how Europe decides to deal with the sovereign debt of Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy. If relief is provided to Greece, it will surely have to be given to Ireland, Portugal, and Spain. If banks are forced to write off the value of their sovereign debt holdings, they will be forced to raise capital through stock sales, or sell assets. Banks are loathed to raise capital by selling stock, since their stocks are selling at a deep discount to book value. If they choose to sell assets, their balance sheets will shrink, which will reduce future lending. This is a significant point because European companies rely on banks to provide more than 75% of their funding. Less lending will automatically equate to less economic growth throughout the E.U. In contrast, U.S. companies receive only 35% of their funding from banks.

We believe the European Union is facing an insurmountable challenge that can only be partially addressed. In recent months, European banks have experienced increasing difficulty in rolling existing debt, as U.S. money market funds have significantly reduced their exposure, and banks in Europe curtailed lending to each other. The European Central Bank has addressed this problem by expanding its lending to more than $650 billion to banks in Ireland, Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and France. The bigger problem is how Europe decides to deal with the sovereign debt of Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy. If relief is provided to Greece, it will surely have to be given to Ireland, Portugal, and Spain. If banks are forced to write off the value of their sovereign debt holdings, they will be forced to raise capital through stock sales, or sell assets. Banks are loathed to raise capital by selling stock, since their stocks are selling at a deep discount to book value. If they choose to sell assets, their balance sheets will shrink, which will reduce future lending. This is a significant point because European companies rely on banks to provide more than 75% of their funding. Less lending will automatically equate to less economic growth throughout the E.U. In contrast, U.S. companies receive only 35% of their funding from banks.

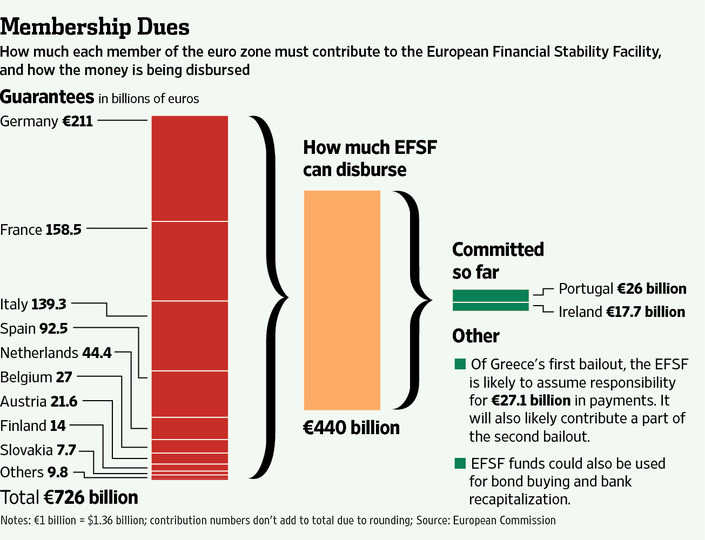

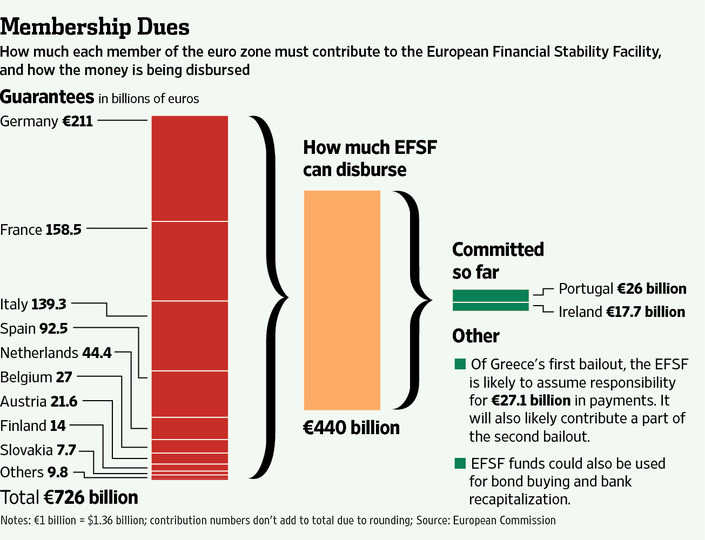

In order to fund the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), the countries in the E. U. will be required to contribute funds, in proportion to the size of their economy. Each country will be increasing its total amount of debt, which in the case of France, may result in a down grade by the rating agencies of its debt. As it stands, the EFSF will be backed by $1 trillion in guarantees, and be able to lend out $550 billion. However, that may not be enough, if Spain or Italy runs into trouble. That is why plans to increase the EFSF to $2 trillion are being considered. By creating even more debt through the EFSF, banks will be able to write off most of their discounted sovereign debt holdings. Maybe we are too burdened by common sense to appreciate the grand design of the EFSF. The absurdity of creating more debt to replace old bad debt is a plan only a fool or politician could embrace. Of course, Europe is being counseled by Timothy Geithner, so we shouldn't be surprised.

In order to fund the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), the countries in the E. U. will be required to contribute funds, in proportion to the size of their economy. Each country will be increasing its total amount of debt, which in the case of France, may result in a down grade by the rating agencies of its debt. As it stands, the EFSF will be backed by $1 trillion in guarantees, and be able to lend out $550 billion. However, that may not be enough, if Spain or Italy runs into trouble. That is why plans to increase the EFSF to $2 trillion are being considered. By creating even more debt through the EFSF, banks will be able to write off most of their discounted sovereign debt holdings. Maybe we are too burdened by common sense to appreciate the grand design of the EFSF. The absurdity of creating more debt to replace old bad debt is a plan only a fool or politician could embrace. Of course, Europe is being counseled by Timothy Geithner, so we shouldn't be surprised.

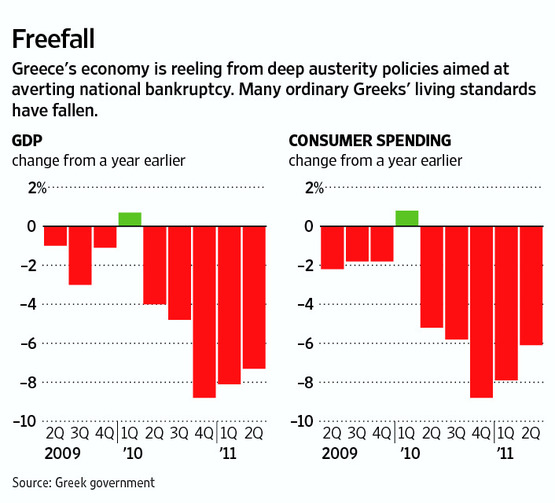

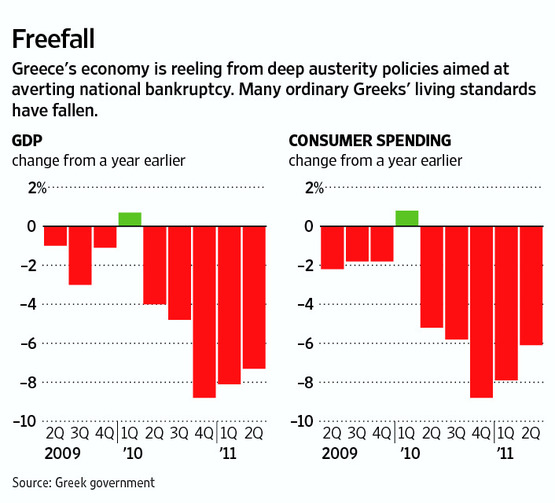

According to figures from the World Bank, for the seven years between 2001 and 2007, the countries in the European Union with the highest average GDP growth were Ireland's 5.44%, followed by Greece's 4.24%, and Spain's 3.41%. As we know, too much of their growth was funded by debt. Not one of these countries grew in 2010. The austerity measures Greece has been forced to adopt has caused its economy to continue to shrink in 2011, which is only making its debt to GDP ratio worse. However, the countries that will shoulder the greatest share of funding for the EFSF did not grow much over the last 10 years. The 10 year growth average for Germany was .9%, France averaged 1.14%, and Italy just .28%. There is a good chance that growth throughout the E.U., and these three countries, will be weaker during the next decade, and especially the next three years. Weak economic growth will make it difficult to service all the old and new debt.

According to figures from the World Bank, for the seven years between 2001 and 2007, the countries in the European Union with the highest average GDP growth were Ireland's 5.44%, followed by Greece's 4.24%, and Spain's 3.41%. As we know, too much of their growth was funded by debt. Not one of these countries grew in 2010. The austerity measures Greece has been forced to adopt has caused its economy to continue to shrink in 2011, which is only making its debt to GDP ratio worse. However, the countries that will shoulder the greatest share of funding for the EFSF did not grow much over the last 10 years. The 10 year growth average for Germany was .9%, France averaged 1.14%, and Italy just .28%. There is a good chance that growth throughout the E.U., and these three countries, will be weaker during the next decade, and especially the next three years. Weak economic growth will make it difficult to service all the old and new debt.

| | | | | | | | | | | 10 yr | 7 yr |

| Country | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | Ave. | Ave. |

| France | 1.80 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 2.50 | 1.80 | 2.50 | 2.30 | 0.10 | 2.70 | 1.50 | 1.14 | 1.81 |

| Germany | 1.20 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 1.20 | 0.80 | 3.40 | 2.70 | 1.00 | 4.70 | 3.60 | 0.90 | 1.30 |

| Greece | 4.20 | 3.40 | 5.90 | 4.40 | 2.30 | 5.20 | 4.30 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 4.50 | 2.42 | 4.24 |

| Ireland | 5.70 | 6.50 | 4.40 | 4.60 | 6.00 | 5.30 | 5.60 | 3.50 | 7.60 | 1.00 | 2.60 | 5.44 |

| Italy | 1.80 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.50 | 0.70 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 1.30 | 5.20 | 1.30 | 0.28 | 1.14 |

| Portugal | 2.00 | 0.70 | 0.90 | 1.60 | 0.80 | 1.40 | 2.40 | 0.00 | 2.50 | 1.30 | 0.68 | 1.14 |

| Spain | 3.60 | 2.70 | 3.10 | 3.30 | 3.60 | 4.00 | 3.60 | 0.90 | 3.70 | 0.10 | 2.10 | 3.41 |

So, the biggest problem facing the European Union is not coming up with enough money for the EFSF. The biggest problem is weak economic growth, which is why the old debt became bad debt, and why Europe is facing a sovereign debt and banking crisis. It is also why a good portion of the new debt will eventually become bad debt too. We don't know how long it will take for investors to reach the same conclusion. But when they do, it won't be pretty. The Euro will fall below 125 at some point in 2012.

China

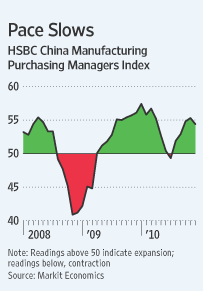

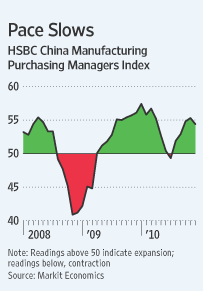

In 2009 and 2010, the state owned banks in China lent $3 trillion, or roughly 60% of China's $5 trillion in GDP. As noted previously, that much lending is sure to end with problems, since bankers are bankers. Some of that lending surely created more export capacity, and with Europe and the U.S. likely to flirt with recession in 2012, China is going to have a problem with excess capacity. The European Union is China's largest trading partner. In September, exports to the E.U. were down from an increase of 22% in August to 10% in September. Since late 2010, China's purchasing managers' index has been falling, and in September dipped below 50. In August, retail sales fell in Brazil, and car sales dropped 5% in September from August. A composite of leading indicators that combines industrial, monetary, and market indicators has been falling for months in Brazil, India, China, and Indonesia, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

In 2009 and 2010, the state owned banks in China lent $3 trillion, or roughly 60% of China's $5 trillion in GDP. As noted previously, that much lending is sure to end with problems, since bankers are bankers. Some of that lending surely created more export capacity, and with Europe and the U.S. likely to flirt with recession in 2012, China is going to have a problem with excess capacity. The European Union is China's largest trading partner. In September, exports to the E.U. were down from an increase of 22% in August to 10% in September. Since late 2010, China's purchasing managers' index has been falling, and in September dipped below 50. In August, retail sales fell in Brazil, and car sales dropped 5% in September from August. A composite of leading indicators that combines industrial, monetary, and market indicators has been falling for months in Brazil, India, China, and Indonesia, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

In our January letter, we discussed how rising inflation was going to force the central banks in Brazil, China, and India to increase rates further to curb the inflation pressures that were building in their economies. "One of the keys to 2011 is that the central banks that have already raised rates will be forced to increase rates more, or take other tightening steps to address inflation in their countries. At some point, it is going to dawn on folks that growth in the second half of 2011 will be negatively impacted in these countries that have been leading the growth parade. Slower growth will also mean less demand for raw materials, and that should lead to a shakeout in copper, oil, silver, gold, and everything else that has been swept up in the global growth story."

In our January letter, we discussed how rising inflation was going to force the central banks in Brazil, China, and India to increase rates further to curb the inflation pressures that were building in their economies. "One of the keys to 2011 is that the central banks that have already raised rates will be forced to increase rates more, or take other tightening steps to address inflation in their countries. At some point, it is going to dawn on folks that growth in the second half of 2011 will be negatively impacted in these countries that have been leading the growth parade. Slower growth will also mean less demand for raw materials, and that should lead to a shakeout in copper, oil, silver, gold, and everything else that has been swept up in the global growth story."

Stocks

The current rally will last as long as institutional investors believe the U.S. will not dip into recession, and that Europe is on the path to containing its sovereign debt and banking crisis. This perception will keep selling pressure muted, and probably squeeze some sideline cash into the market. While concerns about a recession in the U.S. and Europe may take a back seat for a few weeks or even months, we believe fears of a recession in the U.S. will return, and be warranted.

Although the S&P may eventually approach 1300-1320 by mid December, our guess is that a dip in the S&P to 1075-1090 will occur, before the market pushes higher. Sentiment is still fairly cautious, which is supportive. If you didn't do any selling when the S&P broke below 1258 on August 2, we would suggest selling into strength if the S&P trades between 1230 and 1270. It is possible that this rally will end as quickly as it began, if Europe doesn't get it together, and worries about the U.S. economy resurface sooner rather than later.

Dollar

In our May letter we recommended going long the Dollar via its ETF (UUP) at $21.56, and in our July 31 Special Update, we suggested adding to the UUP position below $20.91. We think UUP will trade above $23.00 in coming months. Use a stop of $21.10.

Bonds

As long as the 10-year Treasury yield is below 2.45%, we view it as a warning sign of further banking problems in Europe, and economic weakness in the U.S. Since hitting a low of 1.70%, the high has been 2.27%.

Gold

Gold fell below $1700, which turned the intermediate trend down. A decline below the recent low at $1534.00 seems likely. It would be ironic if it developed if the E.U. announces it has a plan to address their sovereign debt and banking crisis. We would recommend buying gold if it dips to $1510.00, using $1475.00 as a stop.

Macro Tides

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon LinkedIn

LinkedIn